by MGI Staff Report

During a recent Kwanzaa Cultural Access Center & Torchlight Academy sponsored program focused on Black Builders and Designers, audience members were enthralled as four men with historic ties to Macon’s infrastructural and architectural design took to the stage of the historic Douglass Theatre to stimulate and educate those present.

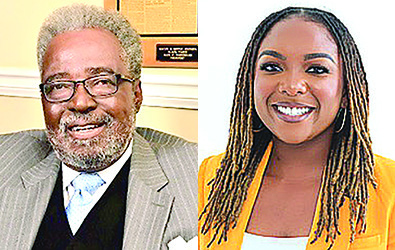

Coordinated and hosted by KCAC president and co-founder George F. Muhammad the program included a panel discussion featuring Clarence Thomas, Sr., a retired master brick mason; historian, educator, and researcher Dr. Thomas Duval; Kirk Hodges, construction expert and owner of Homeland Village; and Shawn Stafford, founder of Stafford Builders and Consultants in Macon.

Muhammad initiated putting the program on for several reasons including the community’s lack of knowledge and appreciation for the contributions of Black builders and as a significant recognition of their contributions at the urging of Macon’s first Black Mayor C. Jack Ellis. Many were unaware until the event that we owe the city’s sewage system to the efforts of men of color. Or that notable buildings like the Hay House and other in-town homes and storefront businesses wouldn’t exist without the brilliance of Black builders.

Dr. Thomas Duval has researched and vested heavily in making sure that many of the relatively unknown and underappreciated Macon historic figures have a place in the city’s pantheon of important people. His four-volume coloring book contest activities includes Macon born architects Louis Hudson Persley of the historic Pleasant Hill neighborhood and Wallace Augustus Rayfield.

Persley is most famous for several churches he drew plans for throughout the southeast, being Georgia’s first Black registered architect, and co-founding the country’s first Black owned architectural firm with Robert R. Taylor. Persley was so formidable as an architect that Booker T. Washington, the founder of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, summoned him there to teach his Carnegie Institute of Technology acquired craft and design several campus buildings.

Like Persley, the craftsmanship of churches throughout the south by Rayfield are still viewable. One of his masterpieces the Pythian Temple –which once graced Cotton Ave downtown – unfortunately isn’t. When it did the multi-use building that housed professionals, a hotel, restaurants, and a parking lot with double entrances served as a testament to Rayfield’s mastery of architecture towering above the Black owned businesses below. So much so that it also served as the headquarters of the Knights of Pythias.

“Macon was a seedbed of Black talent in various trades and professions during the period Persley and Rayfield were creating historic landmarks locally and abroad,” noted Duval. “It’s important to pass this information on to youth especially so they’ll recognize that these local leaders are the wind under the wings of opportunities they enjoy today; and they’ll develop an African American ancestral obligation towards giving back and being great as well.”

Residents get a double dose of greatness when driving the 2900 block of Napier Ave where the Hodges renovated Homeland Village sits right next door to the headquarters of Stafford Builders. Using his background in carpentry Hodges built his business, a cultural and spiritual portal to all things related to education, personal development, and empowerment. And perhaps the only one of its kind in central Georgia.

Stafford Builders has overseen numerous projects throughout Middle Georgia as a contractor and is one of only two Macon based Black owned and operated companies with that ability. The other being Harmon Construction. Bibb Mt Zion Church, Tindall Fields Housing complex, and Cherry Street Lofts are just a few of the buildings developed by Stafford.

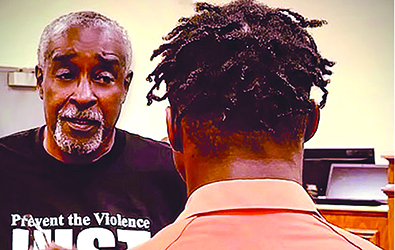

As a proud member of Brick Layers Union #4 in Macon, Thomas and countless other Black bricklayers are owed a debt of thanks according to Muhammad. Not only for the buildings they were responsible for like the Macon Coliseum, William McNeal Turner Post Office, and Middle Georgia Regional Library, but for creating a safe development haven for skill artisans. Some of Macon’s streets reflect Black bricklaying talent, such as the intricately crafted brick section of High Street in front of Saint Joseph’s Catholic School.

Thomas says their strength was in their 200-250 members, unity, and commitment to being bigger than bricks. For instance, their union hall – which sat atop H & H Restaurant and marked with an engraved trough – facilitated meetings for organizations like the NAACP and several local churches. “This union has built a lot of buildings throughout this area. I personally worked on Rocky Creek Road and Bacons Field Shopping Centers, the Medical Center, C & S Bank, and the Macon time capsule holder in front of the Grand Opera House,” he said while holding up a replica of the union’s charter.

“They’re work was absolutely supreme for the betterment of our community,” said Muhammad. “They left a great and powerful legacy that deserves to be recognized, and that our youth should be inspired by.”

Equally important are remaining operational Black owned institutions. The Douglass Theatre downtown is owed to the 1921 vision of Macon born businessman Charles H. Douglass, who opened the theatre and hotel as an entertainment complex for Blacks to enjoy during the Jim Crow era.

The Ruth Hartley Mosley Women’s Center – a French style mini mansion on Orange Street was where its namesake lived and worked as a Black female globetrotting socialite, Entrepeneur, and Civil Rights supporter until her death.

Hutchings Funeral Home, Incorporated at 536 New Street remains a testament to its founder’s vision and resilience since its establishment in 1895. What began as a partnership between C.H. Hutchings, Sr and several other businessmen, continues as a go-to place for laying loved ones to rest.